Beyond Marketing Hype: A Reality Check on the 12 Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems and Warehouse Automation

The hidden costs of goods-to-person systems can be difficult to spot. Since goods-to-person (GTP) systems have revolutionized warehouse operations, particularly for split-case order picking requirements, but do you know the real hidden costs of goods-to-person systems? When implemented correctly, GTP systems deliver impressive results: significant labor reductions, improved facility utilization, and dramatically higher order and inventory accuracy. The marketing materials are compelling, the customer testimonials glowing, and the ROI projections often irresistible.

But behind the polished presentations lies a more complex reality. Many organizations discover critical limitations, unexpected costs, and operational challenges only after committing substantial resources to the purchase and implementation of a system.

“After implementing hundreds of warehouse automation projects, we’ve seen too many companies get caught up in the initial excitement of GTP technology and not the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems and without fully understanding the total cost of ownership. The most successful implementations happen when decision-makers look beyond the marketing materials and honestly assess whether the technology aligns with their specific operational requirements and long-term business strategy,” says Bob Jones, a Senior Consultant with ISD – Integrated Systems Design, a leading systems integrator specializing in warehouse and distribution operations.

This article examines the twelve most critical considerations that potential GTP system buyers should evaluate before making their investment decision. Understanding these factors upfront can mean the difference between a transformational success and a costly disappointment.

1. Product GTP Automated Constraints: The Physical Reality Check

Every cube-based system operates within strict physical constraints dictated by tote and/or location dimensions and system architecture. If your products don’t fit within the available tote sizes or exceed height, width, or length limitations of a certain system, they simply cannot be included in the automation. This seemingly obvious constraint has far-reaching implications.

Products or inventory that can’t fit in with the GTP Automated system require separate picking, storage, packing, put-away, and replenishment processes. This dual-system approach affects every aspect of facility design: labor allocation, storage requirements, warehouse management system (WMS) processes, space utilization, and overall capital investment.

The challenge becomes even more complex during order consolidation. Because GTP systems can operate at high speed, supporting systems must process orders within tight time windows. Other technologies such as WES, buffering, staging, and sequencing systems might or might not be necessary, but this is determined during the design phase.

Many operations have learned the hard way about the hidden costs of goods-to-person systems: that orders arriving at different processing rates create chaos in dock areas and sorting systems, leading to increased labor costs, higher error rates, and missed service level targets across all shipments.

2. Case Picking Integration: Bridging Two Worlds: Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems

Facilities handling both case picking and each-picking face significant integration challenges that mirror the product GTP constraints. The coordination between a GTP system and non-GTP system processes becomes especially critical for less-than-truckload (LTL), full truckload, or corporate truck shipments requiring mixed pallets. Even if a GTP system can do case picking, many times the weight, dimensional limits, or the sheer volume of cases processed force case picking into different areas.

Traditional batch case picking typically operates in segmented waves, while in the GTP automated system, each pick typically runs continuously without wave constraints. These fundamentally different operational rhythms can create timing mismatches that can severely impact efficiency.

Consider a practical example: a customer orders 28-line items consisting of 10 items to be picked from the GTP system (requiring individual packaging, boxing, and labeling) and 18 different SKUs representing 32 total cases picked from a separate case-picking system. How do these disparate order components get reconciled and consolidated efficiently? Multiply this by dozens. hundreds, or even thousands of orders with these same disparate functional processes.

Mixed pallet environments require precise timing and coordination that extends well beyond the GTP system’s scope. These aren’t trivial design decisions; they often determine whether the entire system succeeds or fails. If your operation has these mixed retrieval requirements, either the core automation needs to have the flexibility to handle both cases and splits, or there needs to be other separate systems that coordinate the consolidation processes of mixed orders with significantly varying processing time windows. If your operation requires sequencing (by store, customer, truck, route, etc.,) this becomes “orders of magnitude” more complex.

3. Product Weight: The Overlooked Limitation and One of the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems

While vendors emphasize GTP Automation capacity in volumetric terms, weight restrictions can prove more limiting in practice. Most systems impose tote weight limits around 50 pounds (some higher, some lower), and when products reach this limit before filling all the available space in the tote, substantial GTP Automated space goes unused.

In environments handling dense or heavy products, this weight constraint dramatically reduces effective storage capacity and may necessitate system expansion to compensate for the loss of usable space within totes, which can have significant functional and financial ramifications. Understanding how your specific inventory profile interacts with system weight limitations is crucial for accurate capacity planning and ROI calculations.

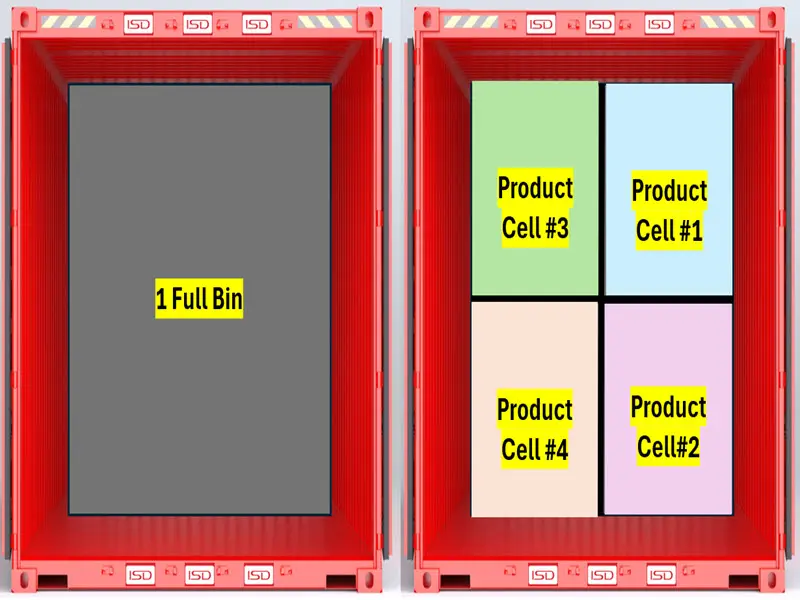

4. Tote Subdivisions: Small Products, Big Challenges

At the opposite end of the spectrum, small and slow-moving items create their own utilization challenges. Many systems employ one or two standard tote sizes, and when a product occupies only a fraction of available space, the remainder goes to waste unless the tote is subdivided.

While most systems typically allow up to eight subdivisions per tote, height constraints mean that even with multiple SKUs, only a fraction of total tote volume may be utilized. The claimed “space efficiency” must be tempered against the reality of your inventory characteristics and tote configurations.

However, the tote subdivision concept also introduces additional operational complexity. When one cell empties and others still contain stock, the entire tote usually is returned to storage for later replenishment of the empty cell – this allows access for the other items in the tote to be accessible for picking. This adds additional transactional load to the system and complexity, potentially requiring additional robots to manage the increased workload.

The challenge intensifies when mixing high- and low-velocity items within the same tote. Poor slotting decisions lead to increased system activity and delays. However, segregating items by velocity requires another layer of management complexity and product assignment, not to mention much less flexibility when pulling totes for replenishment.

Finally, tote cell configurations demand active

management both physically and within system software, including updating WMS and warehouse control system (WCS) or a new WES (Warehouse Execution System) if the application requires help setting (including cell size and locations). These are requirements to manually modify the physical tote divisions, change the tote characteristics within the software, and dynamically balance space allocation between cell size and velocity.

5. Order Flow: The Pace That Determines Success

While product-to-picker flow receives significant attention, order flow is equally critical but often is an afterthought. If orders cannot flow through the system at the required speed, pick targets remain unattainable regardless of the GTP system’s ability to deliver products to pickers. Part of the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems.

Consider the mathematics: if pick requirements require hitting a sustained target of 350 lines per hour with an average order size of two lines, the system must process 175 orders per hour/ per picker—one order every 5.8 seconds in and out of each pick station. If there are 4 pickers, that requires a total order flow of roughly 700 orders per hour (or 1,400 total in and out).

Failure to achieve this pace necessitates additional pickers and more pick stations, directly impacting labor savings projections and system size/cost. This is where we see the most operational issues in terms of the system underperforming and where the labor estimates are understated.

Conversely, larger average order sizes reduce swap frequency. A 15-line average order reduces station changes to once every 2.6 minutes, significantly easing system pressure on the order side of the equation. Hence, the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems.

Order profile analysis becomes critical for system selection and complete process design (including pick stations). While batch processing may help manage flow, it introduces additional complexity, equipment requirements, and costs. However, finding orders with common picks can help reduce transactional load significantly. Again, if orders are accumulated and don’t require a specific process sequence, if the upper-level OMS (order management system) and WES can do the analysis/profiling for common items within orders, it can be a significant benefit. If not, order processing is dynamic and transactional.

To maintain this order flow, the pick stations may need to batch orders dynamically or manually. This offers the GTP system many more options in terms of item retrieval and much more flexibility in terms of timing to the pick stations. These features also can reduce the operator’s waiting for the arrival of products to pick, which could limit hourly transactional rates. However, these pick stations can come at a significant cost and should be developed and implemented with extreme care.

6. Product Flow Consistency: Maintaining Rhythm

Operations lacking long order queues, order look-ahead capabilities, or dealing with volatile order sizes should prioritize product flow consistency during system evaluation and selection. Operations with stable inventory profiles, with a further “look-ahead” for orders in a queue, or fewer constraints on out-the-door timelines, can focus more on density.

7. Seasonal Scalability: Beyond Robot Additions

Most systems tout scalability during peak seasons, typically highlighting the ability to add robots for tote retrieval. However, they often lack flexibility in picking and replenishment stations. Operations needing to scale for example, from three to seven pickers during holiday periods require additional physical stations—manual additions on the fly are not usually possible or practical.

Scalability extends beyond picking stations to include downstream packing and consolidation elements. Replenishment capacity must be scaled proportionally, as systems designed around average daily throughput may encounter bottlenecks during demand spikes.

Careful planning for peak capacity, station availability (inbound and outbound), and the system’s ability to absorb volume fluctuations is essential for maintaining service levels during critical periods.

8. Vertical Space Utilization: Making Every Foot Count

Rack-based systems particularly benefit from full-height utilization, as the loss of space within the racks themselves diminishes and may be erased if the system can utilize height more than other options. Mezzanines or creative retrofits should be approached with caution, as they add cost and complexity. Evaluate how each potential system utilizes your building’s available vertical real estate to maximize return on facility investment.

9. Floor Specifications: The Foundation of Success and a Key in the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems

Floor flatness and smoothness prove critical for robotic movement, especially in systems with vertical lift components (robots that work on the floor but reach higher levels to get totes/cartons). Some systems demonstrate higher sensitivity to floor conditions than others, with cube and stacked tote systems (without racking) or floor-based robots with masts typically requiring the most stringent flatness specifications.

Remediating large floor areas can be extremely expensive and time-consuming, particularly in brownfield sites with existing equipment. Obtain detailed specifications from each manufacturer and conduct professional floor surveys. Align remediation costs, timeline, and feasibility before making system commitments.

10. System Placement and Operational Flow

Most GTP Automated systems don’t allow totes to leave core areas for general processing activities like receiving. Strategic placement relative to docks, receiving areas, packing stations, and staging areas becomes crucial. Remote processes increase transport requirements within the facility, and equipment, systems, and labor required to perform these tasks should be factored into total system costs.

Many failed implementations result from designing automation in isolation without considering the broader operational ecosystem. These GTP systems must integrate seamlessly into existing workflows, not merely occupy their designated footprint. Also, the systems around the automation MUST perform tasks at the expected transactional rates that will not compromise the automation’s ability to perform at the required rates. Implementing an automated GTP system without defining all the operational requirements of the other systems around it is a critical mistake.

11. Fire Suppression: Safety and Compliance Considerations

Fire suppression requirements are critical for both regulatory compliance and insurance coverage. GTP Automated systems create dense storage environments with plastic totes and varied product types. Local fire marshals and corporate insurers may impose stricter requirements than vendors anticipate or disclose.

Sprinkler retrofits, water flow upgrades, and design modifications can significantly impact both costs and implementation timelines. Never assume existing suppression systems are adequate. Engage fire authorities and insurance providers early in the decision process to avoid costly surprises.

12. WMS/WCS/WES Integration: The Make-or-Break Factor and Part of the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems

System integration represents the most critical success factor. Without tightly integrated and well-defined warehouse management systems (WMS), along with a powerful warehouse control system (WCS) or warehouse execution system (WES), even the best hardware will fail to deliver results.

Most traditional WMS platforms, regardless of size or capability, aren’t designed for the real-time, second-by-second control required by automated environments. Goods-to-Person (GTP) systems often require dedicated warehouse control or execution systems to manage real-time aspects around GTP automation. Remember, these automated systems have their own WCS as well, so there will be layers of software.

Manual workarounds that once solved process gaps become impossible in automated environments. Every movement requires software definition, and missing data or broken/nonexistent logic can halt entire operations.

Consider the complexity of replenishing multi-cell totes: the system must understand product dimensions, weights, velocity classifications, and tote configurations. It must pre-stage appropriate totes and orchestrate replenishment without delays. Any failure creates idle labor or system bottlenecks. Successful integration requires accurate item dimensions and weights, comprehensive unit-of-measure mapping for all SKUs, grouping logic for inbound inventory, routing protocols for inbound conveyance, integrated bin and tote sizing with velocity-class logic, real-time WMS/WCS communication, tote routing and validation systems, and full transaction reconciliation between systems.

Making Informed Decisions: A Path Forward From the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems

Goods-to-Person systems offer substantial operational benefits, but they aren’t universal solutions. Successful implementation requires holistic consideration of upstream and downstream processes, data accuracy, physical layout, system controls, robust software implementation, and human factors.

Before committing and knowing the Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems, conduct a rigorous, multi-dimensional evaluation involving stakeholders across operations, information technology, facilities, safety, and finance. Remember that solving problems after implementation always costs more than designing to avoid them.

The organizations that achieve the greatest success with Goods-to-Person systems are those that approach the decision with a clear-eyed assessment of both benefits and limitations. By understanding these twelve hidden costs of goods-to-person systems , you can make informed decisions that align system capabilities with operational realities, setting the stage for transformational results rather than costly disappointments.

The promise of warehouse automation is real, but achieving it requires thorough preparation, realistic expectations, and comprehensive planning, not slick marketing or testimonials that have no bearing on your operation. Take the time to evaluate these factors carefully; your future operational success depends on it.

At ISD, we don’t just sell technology – we partner with you to clearly define your objectives, analyze data, and create tailored solutions that align with your business KPIs and business goals. From conveyors, robotics, ASRS, AMRs, sortation, order fulfillment, and packaging automation, we provide the tools and expertise to maximize ROI and future-proof your operations.

I welcome your questions. For more information, visit www.isddd.com or better yet, schedule a no-obligation consult to discuss your specific concerns and needs and especially The Hidden Costs of Goods-to-Person Systems.